Published on

One of the things about weather that I’ve always found intriguing is that it’s the same for everyone. If it’s raining in New York City, it’s raining on that high-powered CEO just the same as it is the guy selling hot dogs on the corner. Weather is one of the few things in life that puts us all on the same plane, its one of the few things that is able to have an impact on everyone the same way. What’s more, there aren’t too many places around the globe where people haven’t experienced a weather event that they’ll never forget. During my time as an undergraduate at the University of Miami, people still talked about category five Hurricane Andrew as if it happened yesterday rather than some 20 years before. In the northeast, people still talk about hybrid tropical/mid-latitude cyclone (I refuse to call it superstorm!) Sandy. Nobody who was old enough to be paying attention in 2005 is going to forget about Hurricane Katrina any time soon. These are all highly formative events in many of our lives.

When you spend any amount of time in tornado alley, everyone has a story about a storm that impacted them. Its far harder to find someone who hasn’t been at least indirectly impacted by a tornado than someone who has. For many people in Central Oklahoma, this rings especially true. The horrors of all four of the violent Moore tornadoes (1999, 2003, 2010 and 2013) will stick with these people forever. Driving through Moore (and many other areas around tornado alley) the paths are still at least partially visible and are manifest as bare foundations found beside new homes that have been built within the last 20 years. A quick drive up to Greensburg, KS and a similar phenomenon is visible more than ten years after an incredibly violent EF5 tornado tore through the town.

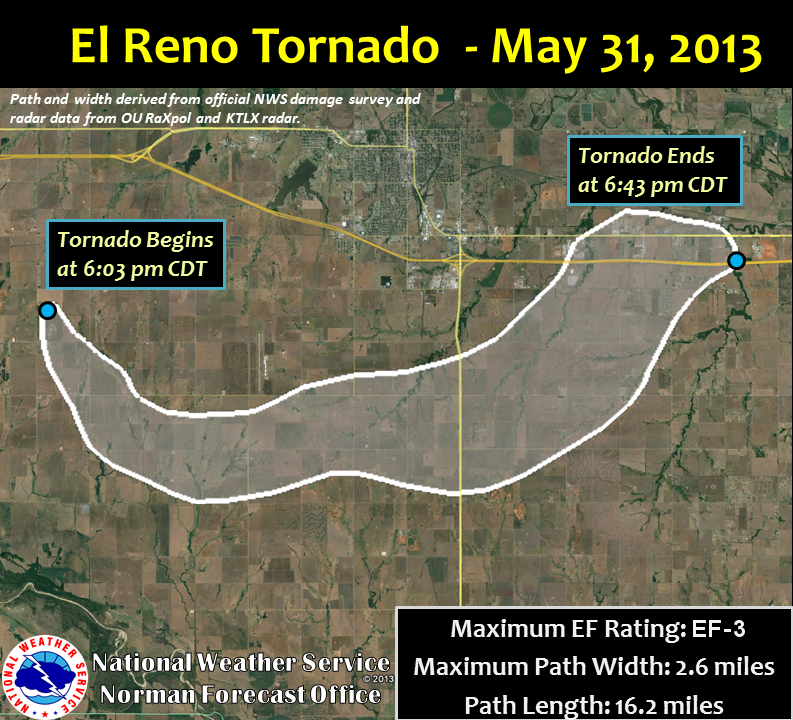

The point of all this is to say that some weather events in your life will always stick out as more significant than others for any number of reasons. Perhaps its because I’m a meteorologist and storm chaser, but I’ve always felt acutely aware of these types of events, and have a rolodex of dates tucked away in my brain. At least as of the time of this writing however, there are two dates that come to the forefront in my mind when considering noteworthy events that I’ve experienced firsthand: May 22, 2011 in Joplin, MO and May 31, 2013 in El Reno, OK. Both of these events were horrifying in their own right, with the former of course ultimately taking its place as one of the most significant tornado related disasters in world history. At least for storm chasers though, you’d be hard-pressed to find an event that sent shockwaves through the community the way that the El Reno tornado did. Following the event, we were all shaken to our depths upon the realization that one of the legends, Tim Samaras, along with his son Paul and chase partner Carl Young were killed by the vicious beast. For me personally, this ranks as the most bittersweet tornado chase.

Unlike the Joplin disaster in which there was really nothing sweet about the event, the El Reno storm was a forecast and chase that I’m quite proud of on a personal level. I had been out chasing for nearly two weeks, and May 31st was set to be my final day on the plains before returning to New Jersey for the rest of the summer. My chase partner Adam and I had spent the better part of the previous three days chasing storm after storm and were fortunate enough to see some really pretty structure and some monster hail. Much like many other storm chases however, we badly needed some redemption. Three days earlier on May 28th, a large tornado sat nearly stationary near Bennington, KS. For a few silly reasons, we sat at Adam’s home in Kansas City. Needless to say, we needed a big day.

On the evening of May 30th, Adam and I got into Oklahoma City after a long day of chasing and checked into what was a much dingier hotel than we’d initially expected. I hadn’t yet looked too in depth into the forecast for the next day, but for several days leading up the GFS was showing a sweet spot in central Oklahoma. As I began to take a look at the forecast, a few things jumped out to me: 1) moisture was not going to be an issue. The atmosphere was pretty much dripping; 2) Instability was downright absurd; and 3) bulk and speed shear looked fantastic but the low-level shear, at least to my eye, was sort of lacking. Around social media, local chasers were raving about the setup and I just didn’t quite see the hype. It was clear I was missing something, and it was pretty simple. In my post-chase exhaustion I was missing the fact that a surface low was forecast to develop just to the west of the Oklahoma City metro, allowing for surface winds to have a more easterly component than I’d seen in individual point-based forecast soundings. This would prove to make all the difference in the world.

The next morning Adam and I woke up and walked outside. The atmosphere had that feel. It was the kind of day where you walked to your car and immediately started sweating. It was both disgusting and exciting. We got a late breakfast at Denny’s (which was far more disgusting than exciting) and discussed the day’s potential. We started reading the SPC forecast discussions and look at model and sounding data. Things were starting to take shape and we started to feel the hype. Our hype however was quickly tempered by the goings-on of a storm that had occurred in the area just 11 days earlier. On May 20th, a violent EF5 tore through the Oklahoma City suburb of Moore. After breakfast, we decided to drift west to watch the cumulus towers develop. In making our way west, we were forced to drive by some of the most indescribably incredible tornado damage I ever hope to see. Cars were wrapped around trees. Entire houses were swept from their foundations. It was a miracle that anyone survived in Moore. Having been in Joplin a couple of years earlier, I knew what Mother Nature was and is capable of, but this proved a somber reminder of the power that the atmosphere possessed. We pressed on however, hoping beyond all hope that we wouldn’t have to see anything even remotely close to a repeat of Moore later in the day.

A few miles out of town, we found a gas station that was apparently home to an impromptu storm chaser convention. To our left was RaXPol, complete with famed tornado research Howie Bluestein sitting in the front seat. As afternoon sun heated the surface, towers began to explode vertically. Not much unlike watching a pot of water boil, the towers would go up and then come down, each time bubbling just a little higher. Finally, a single tower broke through the cap and went up like an atomic bomb. I was sure this was our storm. To this day, I’ve never seen a storm explode the way this one did. Within several minutes, our single tower had developing into an intensifying line of thunderstorms, with three distinct cores visible. Adam and I made a silly choice: we decided to go to the northern core. Any storm chaser worth their salt will tell you why this was a mistake; you always want to be on the southern storm given its typically unimpeded inflow. No matter, we sat and watched as the storm shot up, with the two cores to its south doing the same. Positively charged lightning began to fall out of the anvils of these storms, striking behind our car with such force that each bolt would shake our car upon impact with the ground. Keeping in mind that we were about five miles from any of the cores, this was a pretty wild experience. Looking to the south, we saw a developing wall cloud on the southernmost core and quickly realized we were well out of position. We hopped in the car and frantically began to make our way south. We didn’t make it very far before realizing we’d already been cut-off on the highway by what had now developed into a healthy hail core. On a day with 6000 J/Kg of CAPE, you don’t want to be anywhere near that hail. Luckily for us, we discovered a road a little further to the east that would take us out in front of the storm and began to make our way.

What happened next is something I’ll never forget. As I watched in amazement as the three storms began to amalgamate into a single updraft, I turned to Adam and said, “If these three storms can fully congeal, we won’t soon forget this”. Not five minutes later that very phenomenon occurred, and I would soon find out just how right I was. Keeping in mind the disaster that had occurred roughly 30 miles to the east not even two weeks earlier, there was a tremendous media attention focused on what had begun to unfold. In addition to the local news networks (man of which had storm spotting helicopters flying around the storm) major national news networks were live-streaming the storm all across the country. You can probably imagine my horror upon receiving a phone call from a friend that a tornado was on the ground, and that we were unable to see it. We were too far east and were blocked by the haze in the air. As I frantically looked for westward road options to get closer to the mesocyclone, a single service road appeared seemingly out of nowhere. We blasted west and got right into the hook. Looking off into the distance, we got our first glimpses of the circulation. A faint lowering was visible with what appeared to be condensation fingers dancing below. We were looking right at the tornado. Now admittedly, I’m not much of a photographer. I took out what was effectively a glorified point and shoot camera and was able to snag a couple of grainy stills of the tornado as it approached and began to become obscured by the rain.

As what was now the large swirling mass approached, we realized we were in something of a precarious spot; the circulation was heading directly for us — lucking relatively slowly. We began to weigh our options and were ready to move to the south out of harm’s way. As it continued to approach, we noticed something odd — the storm was starting to move to the north. Given this northward jog, we were able to stay in position as the massive circulation passed about 3/4 of a mile directly in front of us. Suddenly, and as if out of nowhere, the rain parted to reveal what was the largest tornado I, and I later found out the world, had ever seen. It was so big I didn’t even really know what I was looking at. At this point, the inflow wind into the tornado was so strong I couldn’t even close the car door.

After the tornado passed to our north, it once again became nearly completely wrapped in rain and absolutely invisible to any observer. We decided nearly fatefully to try to stay with the storm as it progressed eastward. As we began our trek, we got stuck in a traffic jam unlike any I’ve ever seen. Thousands of people on rural dirt roads on the outskirts of Oklahoma City with a violent tornado in the background isn’t exactly my idea of a good time, and to say I was frightened is a bit of an understatement. To his credit, my chase partner Adam kept his cool and was able to get us out of harms way. We would later find out that a local Oklahoma City TV meteorologist name Mike Morgan had decided to tell his viewing audience that the best course of action in this situation was to drive south out of the path of the tornado, effectively initiating a city-wide evacuation over the course of several minutes. Local roads were backed up to a standstill, as was the interstate which we were forced to take in order to drive south and out of the way of the storm. After what seemed like an eternity of traffic we were able to safely make our way out of the path of the storm and up to Wichita, where we stayed the night.

That evening at the hotel, we began to go over the days events. We were proud of how we handled everything that had occurred. We largely made a good forecast, ultimately picked the right storm and were able to put ourselves in a good and safe position for viewing. Adam and I work really well together as a storm chasing team, and our combination of my navigation and his driving allowed us to have a really good chase day. We were satisfied, even upon discovering the hotel bathroom fixtures weren’t attached to the wall.

The next day was the gut punch. Upon making our way back to Kansas City for my flight, we got the news. We started reading unconfirmed reports of unnamed chasers who had passed away in the tornado. We would soon find out just who those chasers were, and scrambled to get confirmation. I’ll never forget that feeling. It completely negated the excitement we’d felt over the previous 24 or so hours. To lose anyone in a tornado like that, much less a titan like Tim is jarring. This was beyond words. Over the next few days the horrifying details began to become clearer. Like many violent tornadoes, it occluded to the north shortly before dissipating. That same occlusion and jog to the north that allowed us to stay in our viewing position was what ultimately lead to the deaths of three incredible chasers. A running joke in the storm chaser community is that we do what we do “to save lives”. The fact is however, that for the overwhelming majority of chasers this is simply untrue. Tim, Paul and Carl however were different — in order to gain invaluable insight into the inner-workings of tornadoes, they were deploying instrument pods to the north of the circulation. In the process of trying to elucidate the mysteries of these great beasts, they gave their lives for the advancement of the science in an effort to ultimately save the lives of others. We all owe them a great debt of gratitude and should never forget their contribution to the greater good.

Rest in peace Tim, Paul and Carl. You will never be forgotten in this community.

Community Comments

There are no comments on this post

Want to leave a comment? Join our community → OR Login →